If you are a person with only a casual interest in moths, perhaps only seeking the immediate identification of a recently encountered specimen, you may find this website overwhelming and difficult to navigate, much less to understand. If you have a digital photograph of the specimen that you wish to have identified, you may send it by email to MPG. Or you might instead register at BugGuide.Net and post your photo under the ID Request tab.

This portion of the MPG website is for the novice photographer or collector who wishes to become proficient at identifying moths. By using the term proficient I do not mean to imply that you will be helped to become expert at moth identification. But you should be able, using this website, to identify a large majority of your moths at least down to the level of family, subfamily or genus. You should be able, with practice, to be able to determine the species in many, if not most, cases.

There are five plates showing small photographs of more than 1,500 species. Plates are arranged by families and subfamilies but the moths are not identified. As you browse through these plates you'll begin to recognize certain characteristics of the moths. Some families display a posture quite different from other families. Wing shape and patterns of coloration may be evident. And, while size is difficult to ascertain in photographs, the general (not absolute) principle that micromoths are smaller than macromoths will eventually be found to be of importance. In short, by repeatedly browsing through these plates you will begin to develop a feel for what is a Tortricid, Saturniid, Geometrid or Noctuid moth.

As you browse through these plates you might find a moth that is pretty much like what you are looking for. You can click on that photo to be taken to the MPG page for that species where you will probably find additional photos. If you think you have located or are very close to what you are searching for, you should note the species number and then go to the plates for the family or subfamily that include that species. Scroll carefully through that group of moths. You may find several very similar species requiring very close scrutiny. Please also see the caution box at the bottom of this page.

| Plate 1 | Micromoths: Low-numbered Families | 285 photos | 0001-2700 |

|

| Plate 2 | Micromoths: Tortricidae to Pyraloidea, etc. | 329 photos | 2701-6255 |

|

| Plate 3 | Macromoths: Geometridae to Saturniidae | 248 photos | 6256-7770 |

|

| Plate 4 | Macromoths: Sphingidae to Nolidae | 288 photos | 7701-991160 |

|

| Plate 5 | Macromoths: Noctuidae | 390 photos | 931161-933693 |

|

|

Difficulties in Identifying Moths

|

One of the reasons that moths may seem difficult to identify is the sheer number of them. There are about 750-800 species each of birds, butterflies or dragonflies to be found in North America North of Mexico. There are almost 20 times as many moths, perhaps 15,000 species of them. No one knows the precise number. There are approximately 11,500 species already described and given scientific names. There are probably at least 2,000 species known to be present in museum and private collections that have not yet been described (published in scientific journals or monographs). And there is some untold number waiting to be discovered. Brief examples will illustrate this problem.

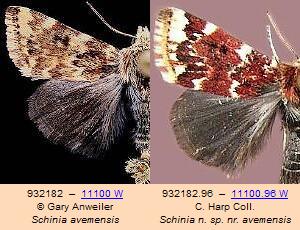

The photographs below were taken from the MPG spread specimen plate illustrating the Noctuid subfamily Heliothinae. We have shown the unnamed moths for a couple of years. The moth shown as Schinia n. sp. nr. avemensis (meaning Schinia new species near Schinia avemensis) will be described and named in a forthcoming MONA fascicle by Mike Pogue and Chuck Harp. They will have several additional new species of Heliothinae to report in that publication, expected in another year or so. Chuck permitted me to photograph his specimen during a visit by him to Washington, D.C.

Tom Dimock and Ken Osborne supplied photographs of another new Schinia species (above) that has been known for several years from the Carrizo Plain area of California. We have shown the photos on a species page titled "11134.4 � Schinia n. sp. � Carrizo Flower Moth � Osborne ms. sp." The notation "ms. sp." indicates that this is a manuscript species to be published soon. In fact, the Journal of the Lepidopterist's Society 64(4) dated December 16, 2010 arrived a week or two ago and included Ken's taxonomic paper officially describing the species now known as Schinia carrizoensis.

New publications, especially new monographs that review genera, subfamilies or families, add extensively to the inventory of species of North American moths. For instance, Jim Troubridge published in 2008 a revision of the noctuid subfamily Oncocnemidinae in which he described 50 new species in the genus Sympistis. Don Davis has in preparation monographs for the micromoth families Tineidae and Acrolophidae which will add upwards of 200 new species to those groups. Such examples make it relatively easy to understand why our present checklists for moths are very far from being "complete."

Maculation, Genitalia, Genetics and Larvae

The term "maculation" refers to the pattern of spots, lines and coloration that we observe on the wing surfaces of moths. These are often, but far from always, sufficient to permit identification at the species level. No one will have any difficulty in identifying the Luna Moth, Actias luna. There is just one species in North America that looks anything like this large green member of the Saturniidae. But, for many species, this is not true. We often encounter pairs or groups of species that are so similar to each other that they cannot be discriminated based on surface characteristics. In such cases we can not identify the moths at the species level based upon photographs. For this reason scientists rely very heavily on examination of the genitalia under high magnification using microscopes and, fairly recently, by also examining the mitochondrial DNA using a procedure termed barcoding. In some cases even these two diagnostic tools are insufficient. To give just one example, there are numerous members of the genus Catocala, popular among photographers and collectors, where maculation, genitalia and barcodes may fail to absolutely identify a species. In such cases the study of the larvae and their host plants might prove to be instructive.

The term "maculation" refers to the pattern of spots, lines and coloration that we observe on the wing surfaces of moths. These are often, but far from always, sufficient to permit identification at the species level. No one will have any difficulty in identifying the Luna Moth, Actias luna. There is just one species in North America that looks anything like this large green member of the Saturniidae. But, for many species, this is not true. We often encounter pairs or groups of species that are so similar to each other that they cannot be discriminated based on surface characteristics. In such cases we can not identify the moths at the species level based upon photographs. For this reason scientists rely very heavily on examination of the genitalia under high magnification using microscopes and, fairly recently, by also examining the mitochondrial DNA using a procedure termed barcoding. In some cases even these two diagnostic tools are insufficient. To give just one example, there are numerous members of the genus Catocala, popular among photographers and collectors, where maculation, genitalia and barcodes may fail to absolutely identify a species. In such cases the study of the larvae and their host plants might prove to be instructive.

Caution, Caution, Caution....

In trying to identify your moth specimens or the moths that you have photographed, you should consider MPG to be a starting point in your research, not an end point in determining a name to be used. While much effort is expended toward making MPG as accurate at possible, you should recognize the difficulties that are strewn along the path of species identification. There are many of them, and the placement of photos on species pages at MPG (spread specimens, living moths, and larvae) should often be considered as tentative, preliminary or provisional. Identification suggested here should always be used with much caution and further research.

|

|

|

|

|